BJJ Prehab Q&A with Lachlan Giles

Heather Raftery

We connected with Lachlan Giles to learn a bit about his journey in jiu-jitsu and physiotherapy, as well as get his expert insight into jiu-jitsu injuries and prevention.

BJJ Prehab Q&A with Lachlan Giles

Lachlan Giles is currently one of the most talked-about Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu athletes on the scene right now. Especially since his spectacular performance at ADCC last September.

The Australian grappler from Melbourne and head of Absolute MMA St. Kilda qualified in the men’s -77kg division after a dominant showing at the Asia-Oceania Trials. He lost in the first round of his division at the ADCC World Championships to Lucas Lepri by mere points. Then Lachlan came back in the absolute division to win bronze, by submitting three of jiu-jitsu’s top-ranked athletes with an inside heel hook. All three – Kaynan Duarte, Patrick Guadio, and Mahamed Aly – weighed substantially more, earning Lachlan the nickname “The Giant Slayer.”

However, he is more than a top level black belt, athlete and coach. Lachlan Giles also has a doctorate in Physiotherapy and his own private practice with wife Livia Giles. As a top physiotherapist in the sports scene, he has worked for Australian Judo Team and numerous football teams.

We connected with Lachlan Giles to learn a bit about his journey in jiu-jitsu and physiotherapy, and to get his expert insight into jiu-jitsu injuries and prevention.

Which came first, jiu-jitsu or physiotherapy?

I started jiu-jitsu at 15 years old and then went on to start my physiotherapy degree at 18 years old.

How long have you been a physio and why did you pursue that career?

I have been a physiotherapist for 12 years now. When I was a kid, I played a lot of sports, and any time I had an injury I would see a physio that my dad knew. At the time, I thought that physiotherapists just work with sports people and it seemed like it would be a good job. Little did I know that for the average physio, most of your time is spent treating non-sports related injuries, and mostly older people.

What was your thesis focus and what did you find?

My research was on patellofemoral (knee cap) pain. There is a common theory that when a particular quadriceps muscle (vastus medialis, VMO) is not functioning correctly, it can lead to this knee cap pain. The first study I did was to measure the size of VMO relative to the other quadriceps muscles. We found that all of the quadriceps muscles were atrophied (smaller) in people with knee cap pain, and it didn’t appear to be selective to VMO. The implications for this was that general quadriceps strengthening exercises are recommended over exercises that try to isolate the VMO (which doesn’t appear to be possible anyway).

After that, I did a randomised controlled trial to investigate the effect of quadriceps strengthening. In particular, I wanted to compare the way it is normally done with quadriceps strengthening using blood flow restriction. Blood flow restriction training is a way of strengthening muscles at lower weight than normal exercises. The theory was that less weight would be more tolerable for patients who had pain. My results partially supported using this… in the more severe cases of the condition.

Does your background in physiotherapy influence your understanding of jiu-jitsu?

It’s hard to say for sure. Certainly, when applying submissions I am quite aware of the way joints move and how to place stress on certain ligaments. That being said, I think jiu-jitsu has done a pretty good job of figuring out the right way to cause injury. Even if unaware of the exact structure the submission is trying to injure.

In your experience, what are the most common injuries in jiu-jitsu?

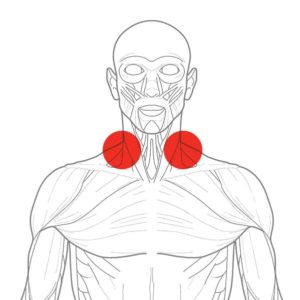

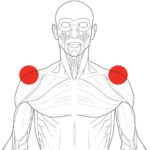

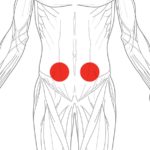

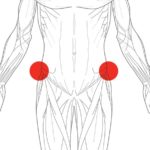

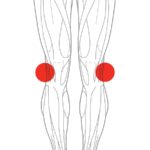

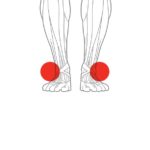

Knee ligament injuries, neck and back injuries are easily the most common injuries in jiu-jitsu. In particular, the ones that all practitioners should be aware of – as they are different to what you would see in a regular population – are LCL injuries of the knee, and a subluxation of the lateral meniscus of the knee. I’ve seen plenty of patients in jiu-jitsu who have these common jiu-jitsu injuries, but were misdiagnosed by their treating physician or physio. This is because they usually assume that such injuries are extremely rare in most sporting populations.

Do you think jiu-jitsu competitors are more prone to injuries?

Competitors are more prone to injuries when compared to the regular population of course. But compared to judo or wrestling, they are probably less so.

Do you see any difference, injury-wise, between points-based rulesets and sub-only?

Overuse/load related injuries are more likely in the gi. You can apply more force while gripping a lapel or sleeve than with no-gi grips. Of course, there are plenty of injuries when heel hooks are allowed. This is because the submission comes on so fast and many people don’t know when to tap.

What tips could you offer jiu-jitsu practitioners for injury prevention while training and/or competing?

1. Tap early, and focus on not getting caught in the submission.

2. Avoid getting stacked and don’t fight the stack (roll with it or relax into it).

3. Unless you are an avid competitor, keep your rolls to a maximum of 80% intensity. The harder the roll the more likely you get injured.

4. Most importantly, keep a steady training load. If you are increasing the load, do it slowly. If your injury allows it, try to train around it. Completely stopping will completely decondition your body to the sport. The boom-bust cycle is horrible for your body.

Heather Raftery is an Atos black belt, freelance writer and social scientist (BA in Journalism and Anthropology, MA in International Studies). She has written for FloGrappling, Jiu Jitsu Magazine, Fighters Market and BJJ Prehab.